Home

Researchers for Memorializing the Enslaved have uncovered a large amount of information on the enslaved people of Arlington including many names, dates, and locations of bondage, and when possible, familial relationships.

17th and 18th Centuries

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, transatlantic slave traders brought millions of captured African people to America. In Northern Virginia, importation reached its height by mid-18th century, but slowly ebbed, as the enslaved population began growing through natural reproduction.

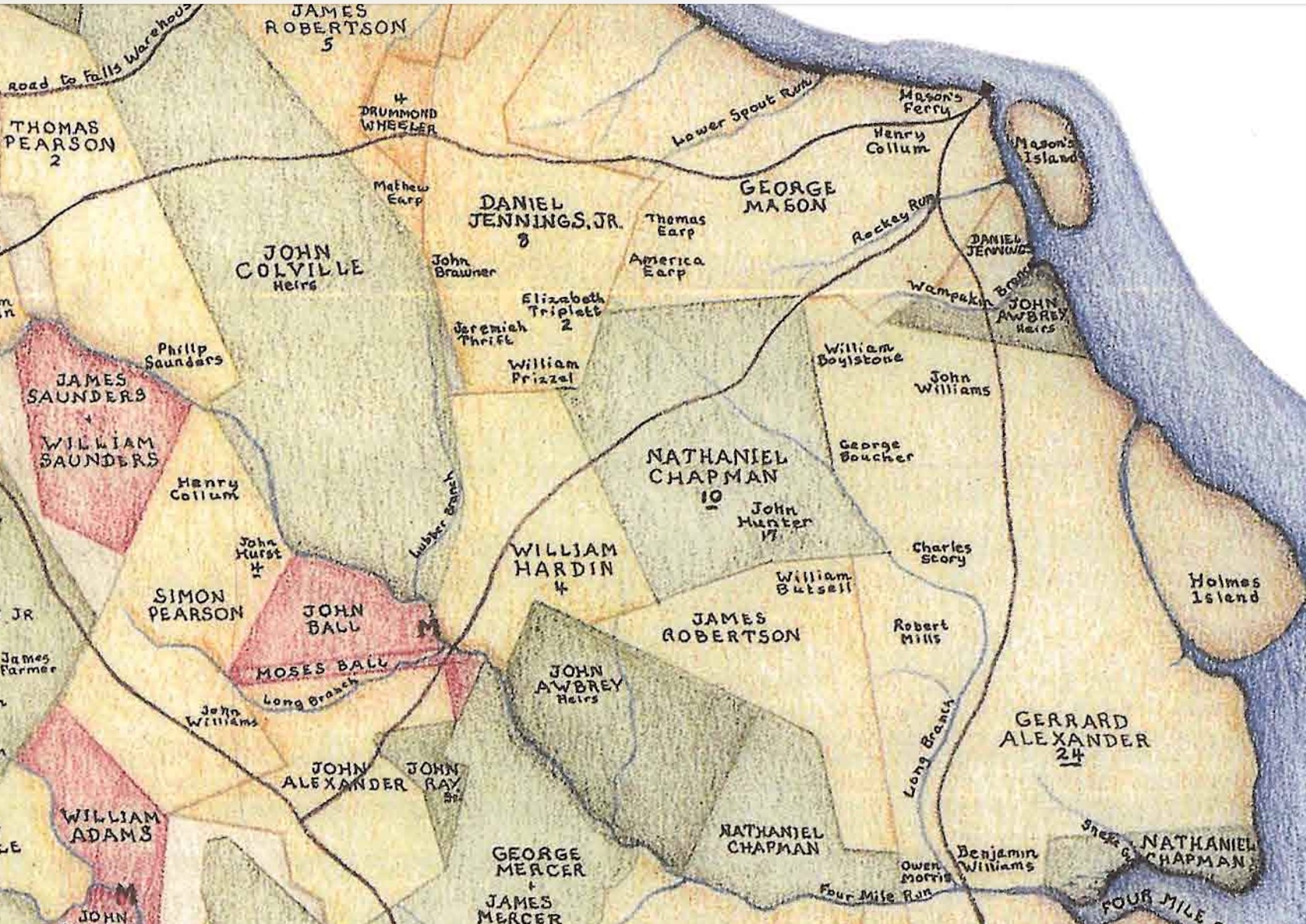

Throughout the 18th century, about a third of Arlingtonians (then residents of Fairfax County), used enslaved laborers to farm the lightly populated area. In contrast, half of all Virginians enslaved others, as did 20% of all American colonists. Most farms in Arlington were small and operated by yeoman planters who enslaved small numbers of men and women or hired laborers from larger nearby farms.

Arlington’s enslaved men, women, and children worked long hours under grueling conditions mostly cultivating tobacco for export or performing endless household duties.

The First Major Plantations

In 1742, Gerard Alexander settled on 3600 acres of land north of Four Mile Run and west of the Potomac River. Through backbreaking toil his enslaved laborers, James, Will, Milley, Nan, Stice, Bess, Rose, Solomon, Peg, Nell, Dick, and Moll, cleared part of the land and created Abingdon, the first major “plantation” in Arlington. It sat on what is now Reagan National Airport.

From 1778 to 1782, John Parke Custis, and his wife Eleanor owned Abingdon and maintained it with at least 70 enslaved individuals. Custis, the son of Martha Washington, died in 1782, but his widow kept Abingdon until 1792. George and Martha Washington were frequent visitors.

Another large plantation was Torthorwald, the summer residence of John Carlyle, located in what is now Fairlington. His enslaved people bred horses, farmed, and operated a grist mill there. At the time of Carlyle’s death in 1780, he enslaved 43 individuals.

Labor Changes

Tobacco production strips the soil of nutrients. By 1800, Arlington’s farmers turned to mixed farming, the growing wheat, corn, rye, fruits and vegetables and tending livestock. Enslaved workers took on new responsibilities such as dairy farming, sheep husbandry, and orchard management. Fewer farm hands were needed. This resulted in a surplus of enslaved people. To remain profitable, enslavers often chose to sell this “excess” property to slave traders.

Domestic Slave Trade

The rise of the Domestic Slave Trade was one of the most barbaric and shameful chapters in American history. The end of the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808 combined with the need for laborers in the Deep South created a market for human trafficking that slave traders greedily filled. Sanctioned by the federal government and leveraged by northern banks, slave traders separated hundreds of thousands of enslaved people in the Chesapeake region from their loved ones and sold them to enslavers in the Deep South. Many of Arlington’s enslaved individuals were transported in chains to cotton and sugar plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana.

Franklin & Armfield of nearby Alexandria, the largest slave trade company in the Chesapeake area, force marched or shipped South 1000-2000 enslaved people every year between 1828-1836. Through careful advertising and the employment of agents, they “professionalized” the business of human trafficking.

Arlington House

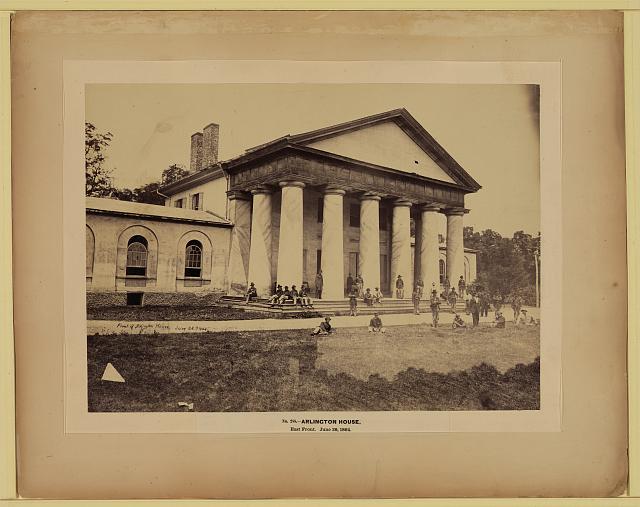

From 1802-1816, George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson and adopted child of George and Martha Washington, and the father-in-law of Robert E. Lee, used enslaved laborers to build the largest plantation in the county, Arlington House.

Until his death in 1857, Custis and his wife Mary enslaved over 235 men, women, and children. Many descended from the enslaved families of Mount Vernon. The enslaved people maintained the Greek Revival mansion and 1100-acre estate while providing personal service to the family. Some descendants of these enslaved families live in Arlington today.

Other major enslavers in the county included Alexander and Louisa Hunter, the owners of Abingdon and Summer Hill, James Roach of Prospect Hill, and Bazil Williams of Prince Seaton. Though enslavers dotted Arlington's landscape, the majority held fewer than five individuals.

Arlington National Cemetery and Freedman's Village

During the Civil War, Union troops occupied the Arlington Estate and transformed it into Arlington National Cemetery, our nations most hallowed ground. The estate also became the site of Freedman’s Village, a community for previously enslaved people. The village evolved into a thriving hamlet with schools, hospitals, churches and social services- providing a model for other freedman’s communities throughout the south. In 1900, the US government closed the village to provide additional land for Arlington National Cemetery. Residents were forced into increasingly segregated neighborhoods such as Queen’s City, Green Valley, and Johnson’s Hill.

The End of Enslavement

The 1860 census, enumerated a year before the Civil War, lists roughly 265 Arlingtonians as enslaved. On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation, essentially freed these men, women and children- ending almost 200 years of human trafficking. On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment finally, permanently, abolished enslavement in the United States.

Neither the 13th Amendment, nor subsequent legislation, meets the promise of true freedom and equality. This struggle continues as citizens continue the hard work of creating a truly colorblind society.

Forgotten No Longer

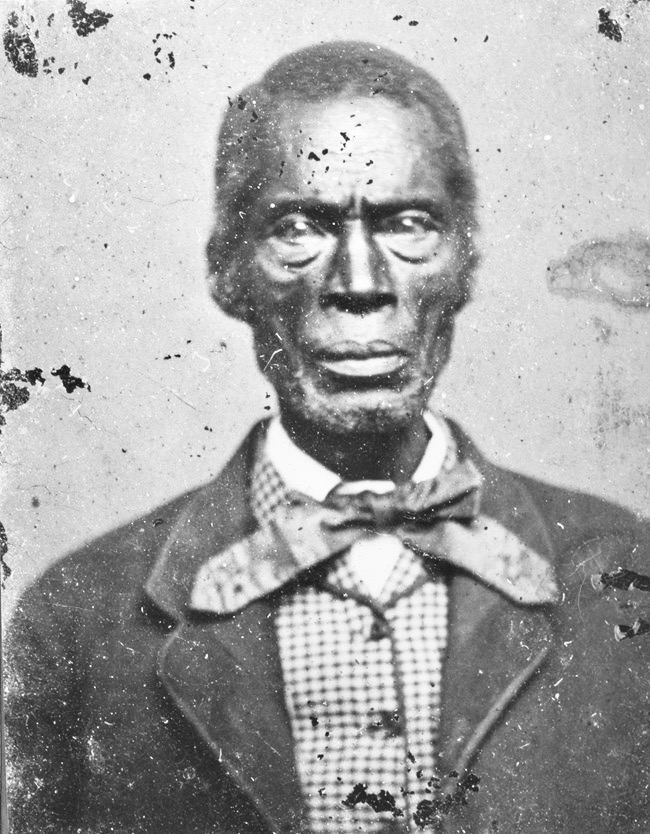

During Arlington’s nearly 200 years of enslavement, White society documented the lives of Black Americans as they would property. By doing so, they effectively buried the identities and contribution of Black individuals.

Memorializing the Enslaved in Arlington is revealing, when possible, the names and life stories of the Black men, women, and children, once enslaved here, who provided wealth to generations of enslavers and nurtured the roots of Arlington’s prosperity.